Editor's Note: Personally it took me a long time to grapple with this subject matter. A person died, who I never truly knew, who I had never even truly witnessed, and yet I still felt this profound sense of loss. How? Why? Is this something I can express without seeming insincere or contrived or overly emotional? I'm not sure. But, in honor of Stanley Frank Musial (1920-2013) and St. Louis I figured I'd try. Here goes nothing.

You’re probably not from here, which means that you don’t understand. And that’s OK. I can’t blame you. It’s not your fault. People cannot choose where they are from anymore than they can choose who their parents are or what color there skin is. Hometowns don’t work like that. They are something you are born into, they are something that you are forced to adopt. Not even wishing upon a star can change the place that will--one way or another--always be your home.

Stan Musial isn’t from here either. He’s from a little town 28 miles or so outside of Pittsburgh, a little town called Donora, Pennsylvania. A little town built on the back of Zinc mills and the immigrants that labored in them. Immigrants like Lukasz Musial, Stan’s father, a man who worked so hard that the mills claimed his life in 1948. A man whose death cemented his son Stanley’s decision to get as far away from those very same mills as he possibly could. Far and away, on the other side of the Mississippi River, where Stan The Man’s legend forever remains sketched in granite.

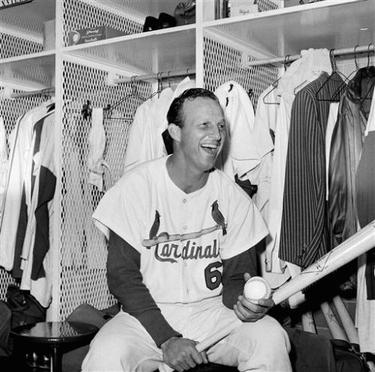

No, Stan Musial isn’t from St. Louis. He is St. Louis. Much like Cal Ripken Jr. is Baltimore or Tony Gwynn is San Diego or Roberto Clemente is Pittsburgh. Only more. Those superstars lived and breathed for their respective cities.

Stan Musial lived and breathed with his, side by side, day after day after day until he didn’t have any more breathe left.

I wish I could paint this picture—the portrait of a hero standing among, not above, the people who worshiped him—more clearly for you, but I know that I cannot.

Stan Musial is St. Louis. Those are the only words I can conjure up to help you understand. But those words are not nearly enough.

In fact if you are not from here, those words probably mean nothing to you at all. And that’s OK. I don’t blame you. It’s not your fault.

It’s just the cold hand of fate deciding that this man belongs to me, and that you would never really be able to know how much that belonging truly means.

You’re probably not from here, which means that you don’t understand. And that’s OK. I can’t blame you. It’s not your fault. People cannot choose where they are from anymore than they can choose who their parents are or what color there skin is. Hometowns don’t work like that. They are something you are born into, they are something that you are forced to adopt. Not even wishing upon a star can change the place that will--one way or another--always be your home.

Stan Musial isn’t from here either. He’s from a little town 28 miles or so outside of Pittsburgh, a little town called Donora, Pennsylvania. A little town built on the back of Zinc mills and the immigrants that labored in them. Immigrants like Lukasz Musial, Stan’s father, a man who worked so hard that the mills claimed his life in 1948. A man whose death cemented his son Stanley’s decision to get as far away from those very same mills as he possibly could. Far and away, on the other side of the Mississippi River, where Stan The Man’s legend forever remains sketched in granite.

No, Stan Musial isn’t from St. Louis. He is St. Louis. Much like Cal Ripken Jr. is Baltimore or Tony Gwynn is San Diego or Roberto Clemente is Pittsburgh. Only more. Those superstars lived and breathed for their respective cities.

Stan Musial lived and breathed with his, side by side, day after day after day until he didn’t have any more breathe left.

I wish I could paint this picture—the portrait of a hero standing among, not above, the people who worshiped him—more clearly for you, but I know that I cannot.

Stan Musial is St. Louis. Those are the only words I can conjure up to help you understand. But those words are not nearly enough.

In fact if you are not from here, those words probably mean nothing to you at all. And that’s OK. I don’t blame you. It’s not your fault.

It’s just the cold hand of fate deciding that this man belongs to me, and that you would never really be able to know how much that belonging truly means.

This piece of writing is not meant to be an obituary. It is not meant to simply tell you that Stanley Frank Musial was born in Donora, PA on November 21, 1920 or that he died in Ladue, MO on January 19, 2013. It’s not meant to just deliver pertinent information, like the fact that Stan was survived by his four children, or his 11 grandchildren, or his wife of 70 years Lil who herself was lost this past May. It’s not even meant to conjure up the image of Stan’s pure, unadulterated greatness or rally around the arm injury that sunk his pitching prospects and forged him into one of the 10 greatest position players baseball has ever known. That has all been said countless times in the past several days. Hopefully you all know at least part of the story by now. The story that is, and should always have been, deeply embedded into American lore.

What you do not know about however is a cold, winter night in the early 1990’s—the date is clearly beyond me at this point—when a young child, maybe 5 or 6 years old, stood at a generic Christmas party in a generic St. Louis suburb wearing a generic green Xmas Sweater trimmed with white reindeer holding the most non-generic thing that has ever been placed in his small hands. A white, crisp, freshly stitched Rawlings baseball covered in Blue ink. Somehow, some way—I think my grandparents perhaps had some connections—I was holding a baseball with the name “Stan Musial” signed in perfect cursive between its cross stitching.

Who was Stan Musial? There was no way I really could have understood. The Man hadn’t walked out of a dugout in 30 years, and had since been replaced by baseball luminaries such as Bob Gibson and Lou Brock and Ozzie Smith and Vince Coleman, names I also may have known—greatness I also never could have, at that point, comprehended.

I never saw Stan Musial play, never saw him lunge forward and uncork a perfect line drive into the left center gap or plow out of the batter’s box like a man whose sole purpose in life was sliding into 3rd base before the other mere mortals around him would have strutted into 2nd. His genius was gone long before he grabbed a pen and scribbled on the baseball that was now sitting squarely in my hands.

Gone, but never forgotten. I remember that December night. I know where that baseball is. I still wrap my fingers around it and feel Stan the Man uncorking one the other way, into the left-center gap, with a swing so pure it was almost as if Abner Doubleday had dreamed about it back in a sleepy New York town when he closed his eye and imagined what his game could become.

Try telling me Stan Musial is just another great player, no different than Honus Wagner or Joe Morgan or Mike Schmidt or Rickey Henderson, and I’ll try telling you that you’re wrong. Yes Stan Musial—like all of those Hall of Fame counterparts—represents the pinnacle of baseball achievement. Yet he is so much more than that.

Stan Musial is The Man who, before I ever figured it out for myself, taught me what baseball, what sport, is.

It was a cold, December night. I was 5 or 6 years old. I held a ball covered in meaningless blue ink. And yet, for no discernible reason, I knew there was so much more to it than that.

And yet, for no discernible reason, I knew that this was what something special felt like. So go ahead and tell me that Musial, while great, shared his greatness with others.

I’ll go ahead and tell you that Musial’s greatness was something no one can ever duplicate: something that was, and forever will be, his and his alone.

Something so powerful that it literally oozed out of his pores. Something so powerful that it will forever remain engrained into everything that he ever touched.

I already knew this at 6-years-old, even though I had no way of really knowing it at all.

There are probably hundreds of stories, anecdotes, and quotes that have been thrown around by writers and television analysts over the past couple of days in an attempt to capture The Man’s essence, and boil it down to one specific moment that shows the kind of man that he was both on and off the field. For instance, Stan was pro-integration, proven in the accounts of 1-Stan seeking out Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Joe Black after a game at Ebbets Field in which a Cardinals teammate directed a racial epitaph towards the mound and apologizing to the rookie hurler telling him “you’re a great pitcher. You’re going to win a lot of games” or 2-Stan seeing a group of black National League All-Stars playing cards by themselves in the back of the dugout and insisting on being dealt into the game, in spite of the fact that he had no idea how to play poker. Those simple acts had a seemingly powerful impact on the people involved—people like Black and Willie Mays—who never forgot a simple kind, decent, human gesture from the game’s greatest ambassador.

Stan also loved his fans. He stayed out in the Cardinals parking lot for hours after taxing August double-headers until he signed every last one of the baseballs that had been thrust in front of him by one of his countless admirers. He played his harmonica for random passerby’s and fellow Hall of Famers and United States’ presidents with the exact same amount of verve and pep, not placing one person in his audience ahead of another no matter their title, success, or standing in the outside world around him. He would shake hands and kiss baby and welcome anybody and everybody into his St. Louis area mainstay—Stan and Biggie’s Steakhouse—with such a genuine appreciation that it seemed like meeting a new customer was paramount to you or I winning the lottery, or at least a couple of bucks off of a fresh batch of scratchers tickets.

On road trips Stan Musial used to visit sick children in the hospital just so he could make them smile. When out on the town The Man carried autographed cards of himself in his pockets and handed them out to kids who passed by without even being asked. In 1998 Stan helped to raise almost $4,000,000 for Covenant House, a St. Louis charity that currently houses 52 homeless young men between the ages of 16-21.

If we are honest with ourselves, then we are willing to admit that we all dream about being famous. Athletes, musicians, movie stars; we watch these people on our TV sets or read about them in Us Weekly or Sports Illustrated and somewhere, in the back of our minds, we become them. We feel the money, the fame, the women (or men) running through our veins, but our true desire rests far deeper than that, all the way down to the place where we can feel the appreciation, the applause, the adoring crowd that cannot help but to admire the genius that we have just put forth publicly before their very eyes. In the place where we feel loved: the place where our hearts are full with the deference and homage given to us by the people we perform for.

Even in our wildest fantasies, we never manage to imagine the other side of things. The drag, the demands, the push-pull of being so loved. The long nights on the road. The frequent appearances and promotion that take away all the time you needed to get to where you are in the first place. The endless stream of fans and admirers, wanting just a second—a photo, an autograph, a kind word—at the exact moment where that simple human effort, probably the 400th or 500th one you’ve been asked to make that day, just does not seem to be worth it. Being unable to eat a meal in a restaurant, or gamble in a casino, or buy a stinking bag of kettle cooked chips at the local grocers without something saying, “Oh, my God…it’s him!!” Being unable to just live for the sake of living.

I don’t feel sorry for famous people, far from it. From the outside looking in, it appears to my eyes as if the advantages far exceed any possible hindrance. But I do wonder if I am not better off without it—the fame. I do wonder how I would handle the pressure, the commitment, the thought of every single move you’ve ever made being analyzed and reported and commented on by someone who swears, if they were in your shoes, they’d do things with a sense of perspective that you—and your rich and famous cohorts—just cannot seem to grasp. And if you are honest with yourselves, then each of you should be wondering the same thing too. Could we do it.

Then there’s Stan Musial: The Man who visited sick kids and signed every autographed and supported worthwhile charities and defused racially tense situations and was just an all-around decent guy to everyone he ever met. He didn’t marry a supermodel or party his way into rehab. He didn’t call the press and have them sell a self-manipulated narrative of his own charitable greatness to the masses. He didn’t draw attention to the way that he lived his life. He didn’t do anything, but be a human being.

As Willie Mays exclaimed when learning of Stan’s passing on Saturday night “I never heard anybody say a bad word about him (Musial), ever.”

No one has. Because people don’t say bad words about the guys who have it all—the guys they dream about being—when those guys are so happy and polite and conscientious that they make us feel lucky that they made it and we didn’t.

Because they honestly deserve this life—and all the trappings that come with it—so much more than we ever could ever hope to.

That’s Stan Musial. The luckiest man we have ever known simply because he is the only one who earned all the luck that he ever got.

Stan Musial used to occasionally eat lunch at the Missouri Athletic Club West in Town and County, located just off the Outer Road that runs North and South along I-270 between Clayton and Manchester. In fact Stan apparently ate lunch there often enough to get a sandwich named after him on the menu. The “Stan The Man” ham and cheese. No frilly olives, no jazzy jalapeno peppers, no wild wild mushrooms. Just black forest ham smothered in melty cheddar. Tried, true, an American classic—just like Musial himself.

In high school I used to eat lunch at the MAC West on occasion as well. Rushing out of school a few buddies and I would pack into my 1999 Ford Explorer and fly down Mason Road, past Highway 40, making a diagonal left turn onto the Outer Road, past the Town and Country police station (where I made more than my fair share of court appearances) and into the MAC parking lot. The whole trip took somewhere between 3 and 5 minutes, depending on the traffic light at Clayton Road. If need be we could leave school, eat lunch and get back in a matter of 45 minutes or so. Usually we’d stick around long after our triple-deck club sandwiches were already sitting squarely in our bellies and drink Arnold-Palmers until we’d have to race to the bathroom on our way out.

More than once during these numerous lunch outings I would look over from our booth—more often than not located in the seating area adjacent to the facilities’ indoor tennis courts—and see a man in a red blazer and a white polo shirt being seated by the hostess at a table right smack dab in the middle of the restaurant. Not a booth stashed back in some corner. Not a private table hidden back in the bar. An open, 4 top with Stan and his guests sitting in plain sight amongst the button-downed professionals out for a quick business lunch and the sports bra wearing suburban moms fresh from their spinning class or tennis lesson.

Every time we saw Stan the Man sitting quietly at that middle-table, my buddies and I would act like giddy school-girls slapping each other and pointing out the legend and peeking over the divider between our booth and his, behaving as if it were a crime to be seen ogling Stan Musial at a public establishment in St. Louis. Just the opposite. The businessmen in the joint, every single one of them, were doing the exact same thing that we were.

No one went up and interrupted Stan’s meal, asking for an autograph or a photo, like they undoubtedly would have in the old days. Things were just a little different now. Stan was older—he was in his middle-to-late 80’s by then—and more subdued. Age had taken a toll on him, like it does on all men who get to enjoy it. You could tell that no one wanted to be the one to come up to Stan’s table and catch him on the kind of bad day that 86-year-olds tend to have now and then. There was too much reverence for The Man to ever risk that possibility.

Yet Stan’s mere presence still managed to suck all the air out of the room. Even while we were pretending not to, everyone was still watching Stan Musial as he sat down and sipped his water. Even as we carried on our regular conversations about school or work or wives or kids we were all thinking the exact same thing. “Holy cow, did you see that!! That’s Stan f***in Musial right there, sitting next to us!”

On one occasion my party and I finished dining while Stan was still seated. As we shuffled out of the restaurant I remember looking at Stan’s table and noticing the sandwich in front of him. From the melted cheddar I could tell that it was an almost completely devoured “Stan The Man” Ham and Cheese.

There is an episode of Seinfeld, which concludes with a shot of the gang in the coffee shop staring at the counter where they see Joe DiMaggio sitting alone on a stool and eating a doughnut. The look on their faces is incredulous and amazed, saying one thing and one thing only: “Holy cow are you seeing this!! That’s Joe F***in DiMaggio, sitting next to us, eating a doughnut!!”

Now, to be fair, I’ve never seen Joe DiMaggio eat a doughnut, but I can guarantee you this: it’s got nothing on watching Stan Musial eat a ham and cheese sandwich.

A ham and cheese sandwich that he put into his mouth and chewed, the whole time having no idea that it carried his namesake.

There are enough stories and quotes and platitudes about Stan Musial to turn this essay into a book, and that book into the bible. I’ve shared some with you here. There are many, many more out there. If you look hard enough you will find something that is new and original and refreshing about one of the most quietly revered men this world has ever known.

But, in the end, I will choose to just leave you with this. There is an old-story from Stan’s playing days about a night where he decided to take his wife Lil out on the town. Anyways the two are out for what is supposed to be a nice, quiet dinner when fan after fan keeps coming up to their table, interrupting their meal and asking Stan for his autograph. Finally, after several intrusions, Lil turned to her husband and suggested that perhaps he just politely decline the next person so they could get on with their night.

“No,” Stan replied. “These are my people.”

Throughout the course of his magnificent 92-years on earth, Stan Musial was a lot of different things to a lot of different people. To his family he was a son, a husband, a father, a grandparent. To the lineup card he was—at different times—a left fielder, a first baseman, a right fielder, and a center fielder. To baseball historians everywhere he was a 7x-batting champion, a 24x All-Star, a 3x MVP, a first-ballot Hall of Famer, one of the best and most underappreciated players to have ever stepped foot on a field. For our country he was a navy veteran. To Joe Black and Willie Mays and a host of other black baseball players he was an “actions speak louder than words” defender of their right to share the diamond with their white counterparts. To sick kids and eager fans and people who lived and died with one swing of his bat everywhere he was a hero, a legend, a God.

And the funny thing about it is Stan Musial may have been the first person to truly earn everything that he meant to everyone that he meant it to.

I first found out about Stan’s death at about 7 P.M. on Saturday night. I was seated in the Scottrade Center for a Blues Hockey Game when a friend in the next seat turned to me and said, simply “Stan Musial is dead.” Instantly I whipped out my phone and tweeted this:

Stan Musial is the greatest St. Louisan to have ever lived…therefore he is the greatest

person to have ever lived. #RIPStanTheMan

This may seem like over-emotional hyperbole to you, and that’s fine. I get it. I don’t blame you. It’s not your fault that you don’t understand that here, in my world, in St. Louis that bit of over-emotional hyperbole is the ultimate, unshakable truth.

We were Stan’s people. He lived and worked among, not above, us.

And that’s how he earned his place as the greatest man this city—my city—will ever know.

And that’s how he became the patron saint of a place that is already named for one.